Gay Games II

Produced and curated by Federation of Gay Games Archivist Doug Litwin and FGG Honourary Life Member Shamey Cramer

with Ankush Gupta, FGG Officer of Communications.

Read the entire "Passing The Torch" series as it is posted daily HERE.

Post 6 of 40 - 2 August - Gay Games II

9 - 17 August, 1986; 3,500 participants; San Francisco, CA USA

“Passing The Torch: Ruby Anniversary Edition” is a factual timeline of the major events that have been part of the Gay Games evolution since its inception. The series will run from 28 July 2022 - one month before the 40th anniversary of the original Opening Ceremony at San Francisco’s Kezar Stadium - through 05 September, the anniversary of Gay Games I Closing Ceremony. All postings will remain online and available for viewing at the FGG website.

* * *

.jpg)

.jpeg)

Opening Ceremony, Gay Games II, 1986

To see video of Executive Director Shawn Kelly speaking at the Closing Ceremony, click HERE

* * *

.jpg)

Australian bowlers at Gay Games II, 1986

DOUG LITWIN: In the lead up to GGII, there was huge excitement in the bowling leagues. At the time, only one team could represent each city. We had a very spirited local tournament to determine which team would officially represent San Francisco. My team lost, so our team entered Gay Games II as representing McKees Rocks, PA, the hometown of my teammate, the late Bill Gaul. We didn’t win a medal but the experience was amazing.

.jpg)

.jpg)

Left: Bands ready to perform at Opening Ceremony. Right: Trapeze performing above the Band at the "Greatest of Ease" concert

I also performed with more than 150 band mates at the Opening Ceremony, a mid-week parade, a sold-out circus-themed concert at elegant Davies Symphony Hall, one or two sporting events, and the Closing Ceremony. An indelible memory was being on stage dressed as a circus clown while a hunky man performed on a trapeze overhead… with no net!

* * *

Photo 1: Jeffry Pike swimming at Gay Games II. Photo: Roy Coe, taken just before Jeffry's bronze medal swim

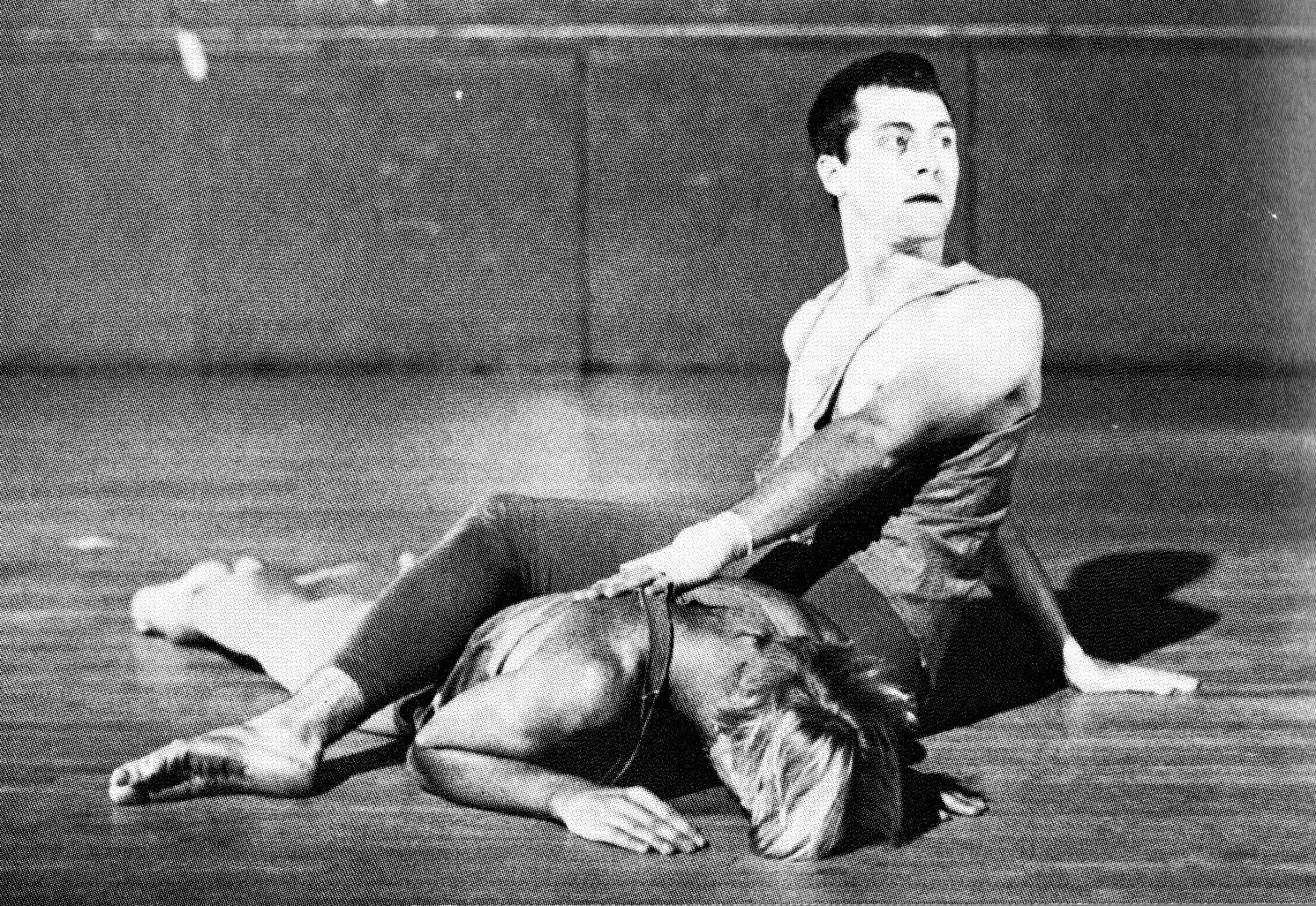

Photo 2: Jeffry Pike and Patrick Kelly performing "Marsupials" (choreographed by Alvin Mayes) at the Gay Games II - Festival of the Arts, August 1986.). Photo; Roy Coe

Photo 3: Gay Games II Closing ceremony with Team Boston pal, Amanda

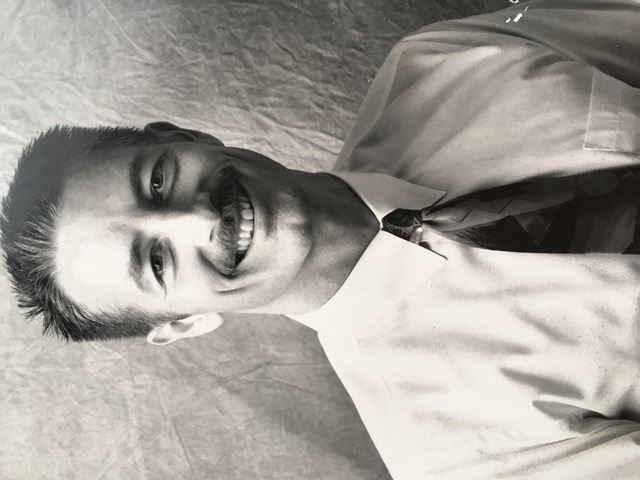

JEFFRY PIKE: When I opened my front door in Somerville, Massachusetts, US, in June 1986, I immediately felt that I had met a kindred spirit. Roy Muir Coe had travelled from San Francisco to interview me for his book, A Sense of Pride: The Story of Gay Games II.

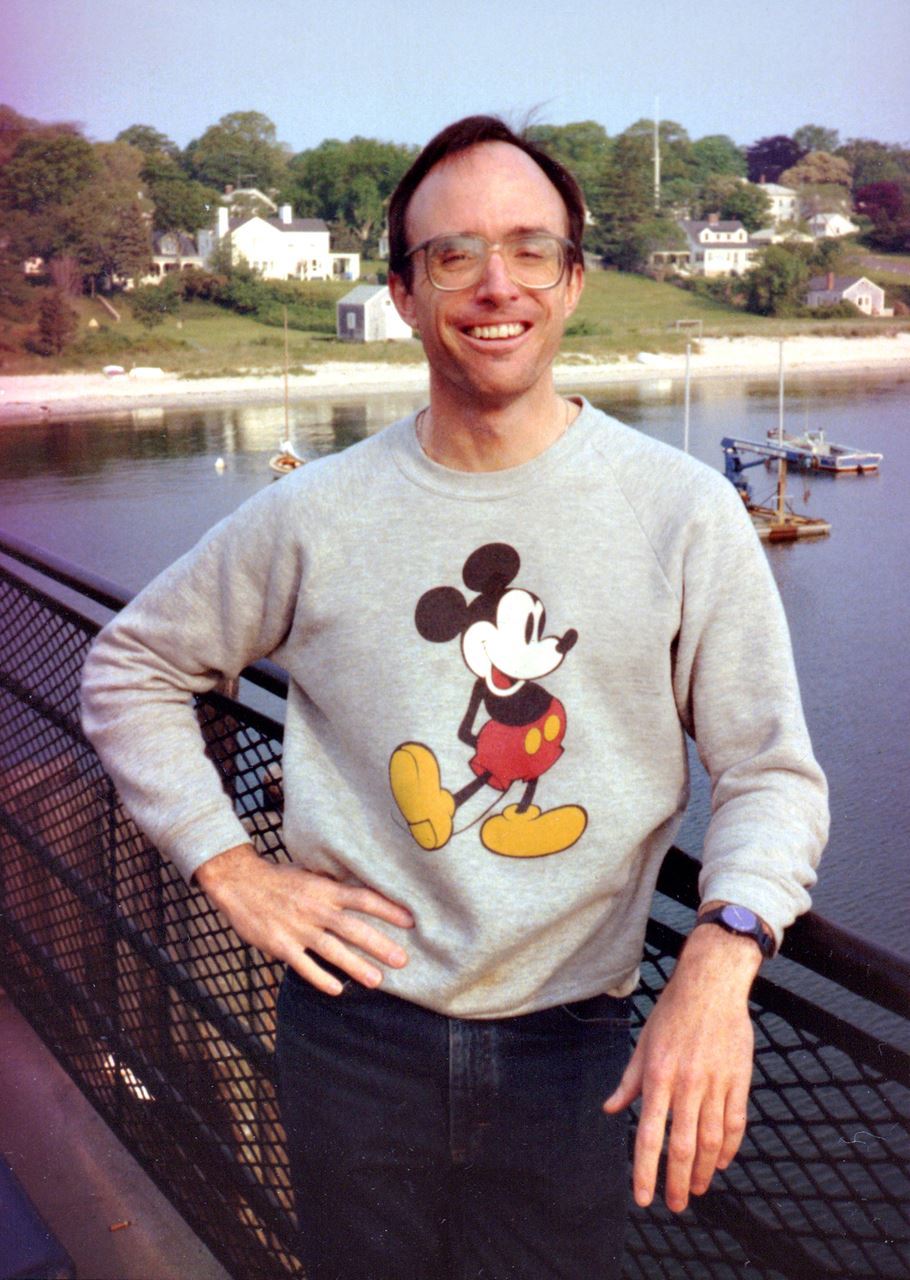

Roy Coe in 1988

In the six years that I knew Roy, before his death in 1992, and the thirty years since, I have confirmed that what drew Roy and me together was our shared search to understand ourselves and our belief in the life changing power of the Gay Games. By inviting each person to tell their story, we all find camaraderie within LGBTQ+ athletics and arts communities, and beyond. In the spirit of A Sense of Pride, for which Roy invited me to tell a bit of my story, in this essay, I will tell a small bit of Roy’s story and introduce some of the people touched by his generosity.

Roy Coe's book (available on Amazon.com)

“In the fall of 1984, I walked into San Francisco Arts and Athletics’ dusty office located in the Pride Center, a former convent which had been converted by the city into offices for Gay Community groups,” wrote Roy in A Sense of Pride. He volunteered to be Communications Director for GGII.

At the same time that Roy worked as Communications Director, he began interviewing athletes and an artist intending to participate in Gay Games II - San Francisco for a book to illuminate their goals and aspirations. In the book, Roy also chronicled, from start to finish, Gay Games II and included a history of Gay Games I - San Francisco (1982). In order to do all this, Roy took a two-year sabbatical from his day job as a computer systems manager. He devoted everything to the Games.

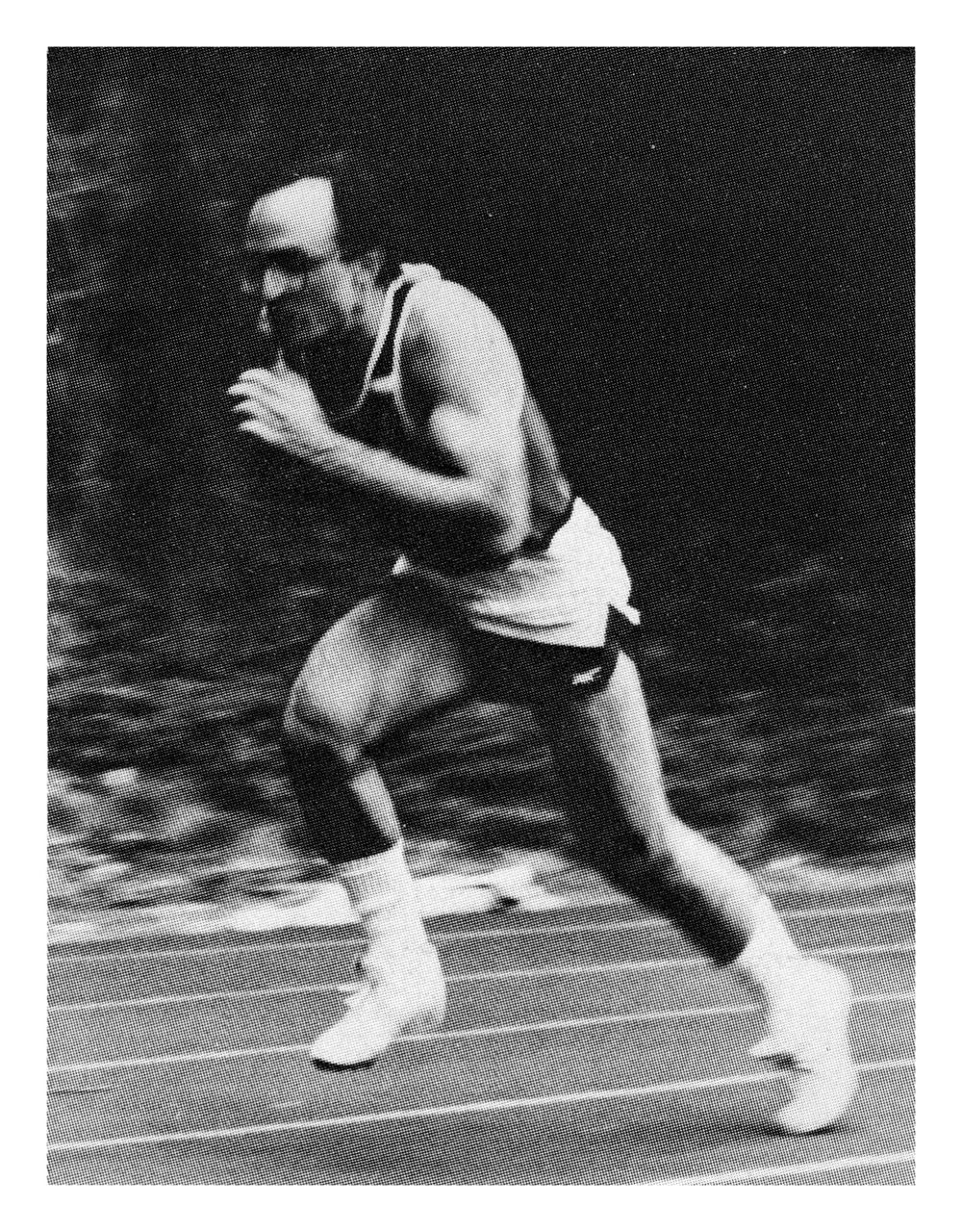

Roy Coe at Gay Games II, 1986

In the introduction to A Sense of Pride, Roy’s motivation for both volunteering for the Gay Games II organization and seeking out other participants’ stories becomes clear. Roy “drew personal inspiration and clarity of purpose” from one particular interviewee’s observations of his own community in Atlanta, Georgia, US.

Roy elaborated, “Simply stated, athletics in the gay community offer hope, spirit, and camaraderie to all who participate. And all are welcome. ... This spirited week (of Gay Games II) represents the culmination of my own desire for community involvement and more positive self-image. I have met hundreds of athletes with similar dreams.”

In Roy’s documenting various details that the organizers faced leading up to the GGII, he reveals that he also became part of a vital close-knit, dedicated team that found solutions as each challenge appeared.

Seemingly tireless, Roy also found time to compete in Track and Field events at the Games and be part of a silver medal winning 4x100 relay team.

After Gay Games II and the publishing of A Sense of Pride, Roy’s involvement in the Gay Games changed to being a supporter of participants and patron of the Cultural Festival of the Games.

When I was invited to be a charter member of the Federation of Gay Games in 1989, Roy, with his experience from GG II, happily became my sounding board and source for perspective on the politics around and historical details related to various Gay Games topics.

When Roy died in 1992, it was revealed that he intended to continue supporting the Games through the endowment of the Roy M. Coe Scholarship Fund. His goal was to ensure that others would be able to attend the Games. He specifically wanted funds to cover travel expenses to bring first-time participants from continents other than the host city’s continent.

* * *

JACK GONZALEZ: Four years later, San Francisco is again the host for Gay Games II. So much seems to have happened in those four years. The mood, while still one of excitement and high energy, is somewhat muted, because no matter how joyous an event we are there for – one cannot forget the epidemic, which in those four years took so many of our friends and loved ones. The Castro District, which is the heart of the Gay community, was still buzzing with multitudes of people (tons of restaurants & bars there). Still buzzing with activity - but not like it was four years prior. It felt like some of the puzzle pieces were missing.

But as they say: the show must go on. This time around, the Los Angeles contingent was better prepared. We were (almost) all wearing an actual team uniform for Opening Ceremony. I requested housing and was set up to stay in the Twin Peaks area. My host, who lived alone, was a very nice and handsome man. He was sick with AIDS. A few years earlier, I may have felt unsafe, but by then, most of us were aware of how the disease spreads, and conducted ourselves accordingly. One evening after tournament play, while sitting around chatting with my host, he asked me if I would object to ‘holding him’. I was a bit taken aback. It did not take me long to understand that he had no human contact with anyone and was very lonely. I did not mind at all - hugging him tight and letting him feel my warmth and humanity.

Volleyball at Gay Games II, 1986

For these Games, I did not put together my own team (volleyball). I played on a friend’s team. I was familiar and friendly with all of my new teammates. By this time, most of the other cities (states) had formed more competitive teams, so we were not favored to win as we were previously. Again, San Francisco did not disappoint with their excellent organizing skills. The facilities, although not located in the Gay Ghetto, were excellent. The tournament itself was well run. I have very little memories of the competition itself. This is most likely due to not winning. My brain has its own agenda as to what it sees as worth remembering. Or so it seems.

I wish I had better memories of these Games. I do recall that although a joyous event for many, there was also the underlying fact that many of us had lost friends... and it wasn’t over. The disease continued to take more of us.

* * *

Jim Hahn (at right in blue shirt) at Gay Games II bowling venue 1986

JAMES HAHN: In Gay Games II, I came as close to winning a team medal as I’d ever come. Our team from San Jose, California made it to the second round of competition and did well coming in 5th. We won the first game of the stepladder finals leaving us just one game to win in order to qualify for a medal. Unfortunately, our best bowler, bowled nearly 80 pins under his average and we missed out. He was so broken-hearted, he went back to his hotel room and cried. He passed away from AIDS about a year later. This proved to be the best competition in bowling, before or since.

* * *

RICK PETERSON:

Swimming for Our Lives -

Gay Games Changed My Life and the Life of our Global Gay Community Forever

Rick Peterson at open water swimming event, 2022

I first heard about Gay Games after Dana Cox, a good friend in my hometown of Seattle, enthused at a dinner party that he’d just returned from the first Gay Games in San Francisco with two gold medals for swimming the 50-yard and 100-yard breaststroke. I was impressed and surprised! I didn’t know that side of Dana! I didn’t realize he swam. I didn’t know about Gay Games, had never heard of it.

Actually, at that time in 1982, I had no perception of any opportunity to participate in Seattle’s emerging gay community as a swimmer or athlete (other than bowling and softball at the time, plus a little volleyball), let alone anything as fantastic-sounding as what Dana described— entering Kezar Stadium along with about 1,500 other LGBTQ+ athletes and artists at the Opening Ceremonies of Gay Games and being serenaded by Tina Turner! I think Dana was the only swimmer from Seattle. I was fascinated.

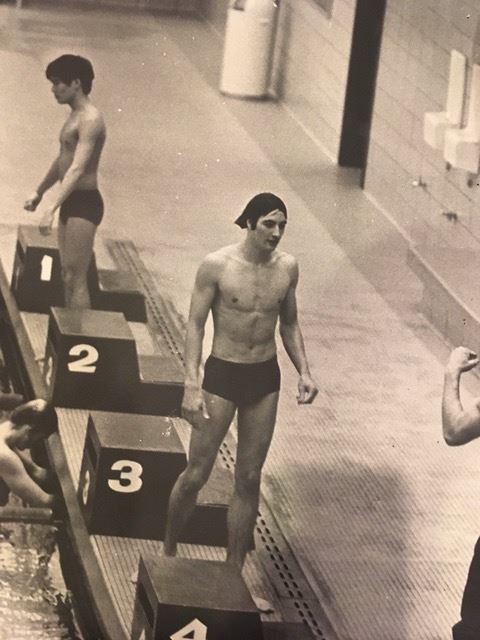

Rick Peterson, Washington State University swimmer

In my “past life” from the time I was ten years old until May 1973 when I graduated from university, I’d been a swimmer. Big time. I was a champion high school swimmer, followed by four varsity years as a NCAA division one athlete on scholarship at Washington State University. But after I graduated, I thought I would never seriously swim again and I was okay with that.

And that’s pretty much what happened. Instead of continuing to “be a swimmer,” I drove to San Francisco cold-turkey from Bellingham, a small town near the Canadian border where I’d grown up as kid, with everything I owned crammed in the car. As I crossed the Golden Gate Bridge, I had no idea I’d landed in an epicenter of emerging Gay Liberation. That was September 1973, just after I’d turned 22.

I kissed swimming goodbye, diving full speed into a blistering decade of coming out, being in a relationship, dancing and having fun at discos, working for the Sierra Club national headquarters, enjoying the unique bliss of being young, healthy and gay in and around the San Francisco mecca. I continued to think of myself as “an athlete” in some sense, at least inwardly. My world view continued to be heavily influenced by years of training as a swimmer, being a part of a team, putting in the effort, honing, self-discipline, being brave enough to put yourself out there to participate and compete at your best, being coachable, being persistent, discovering you can be really good at something if you apply yourself.

Nearly a decade later, after Dana surprised me with his story about participating in the first Gay Games, I started to think about dipping my toe in a pool for the first time since hanging up my suit in 1973, this time at a weekly lap swim at Queen Anne pool in Seattle known unofficially as “gay swim night.” Nothing organized. No-one really competing, mostly just guys and a few gals enjoying staying in shape and getting the “swimmer’s high” of a good self-imposed hour-long workout in a lane you shared with other gay people you did not know until then. New acquaintances! New friends! Swimming feels great! It was so fun to be back in the water—especially in a way that felt safe and welcoming, sharing the magic of gliding through water with kindred spirits.

Orca Swim Club logo

I and a few others, including Dana and John Horman, another friend I’d made through “gay swim night,” decided to form a “gay swim team” for Seattle. This was in 1984. We called ourselves the Emerald Orca Swim Club (Seattle is nicknamed the “Emerald City” for being surrounded by evergreen forests and mountains). I became co-captain and shortly thereafter Allison Beezer joined me as co-captain—a wonderful woman involved with guiding clients on socially-responsible investing and financial planning. One of our biggest first goals was to organize swimmers and divers from Seattle to participate in Gay Games II in San Francisco in 1986. Dana would no longer be the only Gay Games swimmer from Seattle!

To get ready, we needed to not only practice swimming, we needed coaching, we needed pool access, we needed to practice actually swimming in competitions, diving off the starter blocks, having legal turns at the end of each pool length, not getting disqualified for touching the pool end with one hand versus two hands simultaneously as required by USMS rules for breaststroke, etc.

As our Orca Swim Club began to grow, it became clear that we were definitely going to send a dozen or more swimmers to Gay Games II. It also became clear that other sporting interests in Seattle’s growing LGBTQ+ community were emerging and coming into existence—spurred on by the excitement of being able to participate at Gay Games II. A real movement was beginning—a whole new form of “gay liberation” centered on the health, fitness and camaraderie unique to participatory sport. What a thrill and wonder! Given the level playing field unique to sport, we gay men, women and the full spectrum of gender identities could not only hold our own, we could compete with the best.

Rick Peterson at Gay Games II in 1986

Picking up on this burgeoning sport scene, as co-captain of the Orca Swim Club, I began talking with other emerging sport leaders of other gay teams in Seattle including Frontrunners, the volleyball team, soccer team, softball and bowling leagues and more. I and a few others recognized the value of forming some kind of umbrella LGBTQ+ sport organization in Seattle that could help support new and emerging sport teams, and band together to promote the opportunity and excitement of fielding a big multisport team to Gay Games II. So, I helped co-found Team Seattle in 1985 and became co-chair along with women’s soccer player Danette Leonardi.

After Gay Games II, to keep the ball rolling, the Orca Swim Club organized what we continue to believe was the first USMS-sanctioned LGBTQ+ swim meet possibly in the world, or at least up to that point in the United States. We hosted a USMS-sanctioned dual swim meet with our wonderful neighbor LGBTQ+ swim team 2-hours north in Vancouver, British Columbia, the English Bay Swim Club.

It was at this first dual meet in 1987 that the Orca Swim Club introduced the “Pink Flamingo Relay,” a fun way to cap off the swim meet and “make it gay.” Since then, the Pink Flamingo Relay has continued to grow and become a true highlight of every Gay Games aquatics competition—and at annual International Gay and Lesbian Aquatics (IGLA) championships.

Up until this point, swimming at Gay Games I and II was not USMS-sanctioned. No USMS swimming records could be set, nor World Masters records. For that to be possible, swim competitions in the United States had to be sanctioned by USMS, the governing body of masters swimming in the U.S. (with similar country-specific masters organizations globally, comprising World Masters Swimming).

To obtain USMS sanctioning for our first swim meet, we had to overcome unexpected objections from the regional USMS sanctioning body in our area. Usually, getting a swim meet sanctioned was a rubber-stamp kind of thing. But here we were, in a fight with misinformed people prejudiced against gay people, even people who feared we’d spread AIDS in the pool. This was all happening as the enormous and terribly frightening AIDS pandemic was accelerating. Misinformation was rampant. Fear was gripping.

Long story short—with the help of Cal Anderson, the first and only openly gay elected member of the Washington State Legislature at that time—we cried foul, and got our sanctioning. And the rest is history because after that, the Orca Swim Team became one of the most popular USMS swim meet hosts in Western Washington. Stroke by stroke, we began changing the swimming world in our little neck of the woods.

Meanwhile, Team Seattle focused on gathering a huge team to participate in Gay Games III in 1990 not far away in Vancouver, Canada—the first Gay Games outside San Francisco. To build momentum and interest, we organized our first multisport festival in the summer of 1987—dubbed the Northwest Gay/Lesbian Sports Festival. Coordinating with local LGBTQ+ sport teams and leagues, we offered about 15 sports including the first-ever LGBTQ water polo tournament as part of our aquatics line-up, spearheaded by Mark Schoofs from San Francisco. Which then spurred the birth of our first LGBTQ+ water polo team in Seattle so we could participate in our own tournament!

Everything just kept building—now I was a swimmer, a water polo player, co-caption of the Orca Swim Club, and co-chair of Team Seattle spearheading a 15-sport festival on the way to attracting more participants than the first Gay Games in San Francisco (all while holding down a full-time job in the creative department of an ad agency)!

Lots of fitful nights waking up in a panic. The combined experience had a huge impact on my personal and professional life, helped me find inner courage, work with diverse groups of people, find common cause, and discover I had more leadership skills than I’d given myself credit for. The confidence I was able to develop in the LGBTQ+ sports community ended up having a huge impact on my advertising career, as well. Thank you Gay Games.

As our first Northwest Gay/Lesbian Sports Festival was approaching, I learned Dr. Tom Waddell, U.S. Olympic decathlete and Gay Games founder, was set to visit to Seattle for a television interview about the Gay Games and about him having HIV and AIDS. Somehow I was able to make contact with Dr. Waddell and he graciously invited me to meet and have lunch at his hotel prior to his interview.

Tom Waddell was, and remains today, someone I strongly revered and almost idolized. I was greatly humbled to meet him. Really, I was thunderstruck and hardly knew what to say. Tom was such a supremely well-spoken and soft-spoken man, beyond inspirational. He was so enthused and encouraging about our upcoming LGBTQ+ sports festival in Seattle slated for July 1987, totally inspired by Gay Games.

Dr. Waddell and I had our lunch on Feb. 26, 1987. He was already clearly suffering and frail at the time. I wondered how long Tom would live. People were beginning to die left and right as the AIDS pandemic asserted itself strongly, a very frightening time. Without knowing if it could ever happen, I invited Dr. Waddell to come to our first sports festival as a special guest of honor and speaker. But less than five months later on July 11, 1987, Dr. Waddell passed away at age 49, with his last words being, “Well, this ought to be interesting,” according to his wife and fellow Gay Games leader Sara Waddell Lewinstein.

It was terrible to lose the visionary and inspiring founder of Gay Games. But Tom and his fellow members of San Francisco Arts and Athletics had permanently set in motion a movement destined to sweep the global LGBTQ+ world, and really transform what it could mean to live as an empowered member of one of the world’s most historically marginalized groups.

Gay Games founder Paul Mart receiving the Tom Waddell Award at Gay Games III in 1990

Instead of Dr. Tom Waddell showing up at our first Northwest Gay/Lesbian Sports Festival in 1987, another legendary board member of San Francisco Arts and Athletics arrived as our guest of honor instead, the irascible, cowboy-hat wearing Paul Mart. At the conclusion of our 3-day sports festival, we hosted a big closing ceremonies dinner with about 700 athletes attending, and I’ll never forget when Paul Mart presented us with a beautiful, original “Gay Olympic Games” poster, banned by the U.S. Olympic Committee (in fact all such posters were ordered destroyed, but just a few somehow managed to survive, and now, Paul Mart had just presented us with one, with the blessings of by-then-deceased Tom Waddell).

Swimming had again become the deep keel that was keeping my ship upright in a heavy seas. And I wasn’t the only one—by now I knew that many in our LGBTQ+ community were joining swim teams, and all kinds of other new teams all over the world partly in response to the inspiration of Gay Games. As the crushing weight of the AIDS pandemic continued to build, we were all trying to survive and thrive in a scary time. In a sense, we were all “swimming for our lives,” connecting to community, support and strength through sport (and culture, too).

The following summer, Team Seattle hosted the 2nd edition of the Northwest Gay/Lesbian Sports festival, and introduced such sports as fencing and croquet (the latter making it into the roster of Gay Games III sports in Vancouver 1990). Participation grew to more than 1,700 athletes from all over the U.S., Canada, and further afield.

Wisely, in about 1987, Vancouver Arts and Athletics, the organizers of Gay Games III, started inviting known LGBTQ+ sport and cultural leaders from all over North America including some from Europe, to visit Vancouver for intensive 3-day planning conferences to help Vancouver plan the best possible Gay Games III. I was among the delegation from Seattle, joined by fellow Team Seattle board members Margaret Hedgecock and Betty Whitaker.

At these Gay Games III planning conferences I met other like-minded LGBTQ+ sport leaders including some very talented and strong women: Peg Grey from Team Chicago, and Susan Kennedy from Team San Francisco. I was really enjoying getting to know women—women I grew to admire and like very much. This was all fostered by my involvement with Gay Games and our nascent international LGBTQ+ sport and cultural movement. For the sake of continuity and “lessons learned,” key members of the San Francisco Arts and Athletics board also attended these Vancouver planning sessions including Sara Waddell Lewinstein, Paul Mart, attorney Larry Sheehan, and Gay Games II executive director Shawn Kelly.

To see video of Executive Director Shawn Kelly speaking at the Closing Ceremony, click HERE

One day in early 1989 I got an unexpected phone call from Larry Sheehan, co-president of San Francisco Arts and Athletics, the organization Dr. Waddell had founded to produce Gay Games I and II. SFAA was about to rename itself the Federation of Gay Games to make it clear Gay Games didn’t belong to San Francisco, but rather to the world. SFAA planned to expand its board of directors beyond just San Francisco and Bay Area members. These actions would occur at a special SFAA board meeting which Larry proposed to hold in Seattle in early July, 1989.

Rick Peterson, FGG Co-President

He told me that he and other members of the continuing SFAA board of directors would attend including SFAA co-president Rikki Streicher, along with key leaders from Vancouver 1990 including Richard Dopson, and a small group of LGBTQ+ sport leaders involved in Vancouver’s Gay Games III planning sessions. Larry told me I was invited, along with fellow Team Seattle leaders Betty Whitaker and Margaret Hedgecock. He asked if I’d help find a good venue for the meeting (I said “yes”), and then he dropped the bombshell:

“We want to nominate you to be co-president of the Federation of Gay Games."

FGG leadership at Gay Games IV. L to R: Brent Nicholson Earle, Rikki Streicher, Sara Waddell Lewinstein, Susan Kennedy, Rick Peterson

That began a dramatic new chapter in my Gay Games adventures. Including, during the five years I served as FGG co-president, the thrill of seeing Gay Games grow from 3,500 participants at Gay Games II in San Francisco in 1986, to 7,500 participants at Gay Games III in Vancouver in 1990, to 11,500 participants in 1994 at Gay Games IV in New York City. And along the way, breaking barriers and celebrating the development of sport and culture groups— creating exciting opportunities for hundreds of thousands of LGBTQ+ athletes and artists worldwide to participate, be included, and reach for personal bests.

* * *

Read the entire "Passing The Torch" series as it is posted daily HERE.